Cemetery sculpture allegory and pathos

Cemetery sculpture allegory and pathos

From a city monument or from an ordinary memorial plaque, which has historical and documentary significance, the grave monument differs above all in a certain emotional mood. The artistic tombstone “enters into communication” with the person approaching it and requires from him a certain concentration. The intonation of the perception of the monument is usually individual and, as a rule, lyrical, intimate. This gives the monument a special force of influence, and creates around it an atmosphere of a peculiar mood that cleanses the soul. Noteworthy, talking about the departed, the monument always refers to the living.

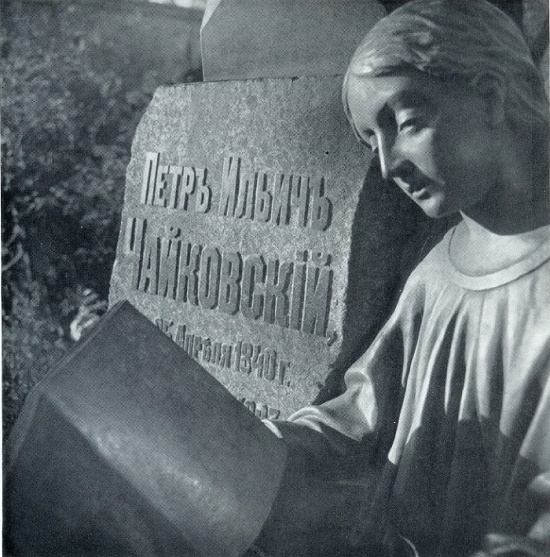

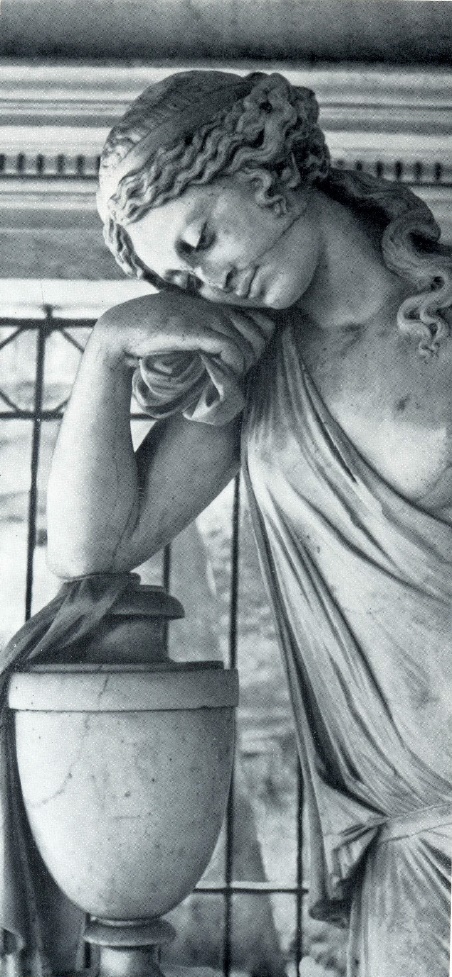

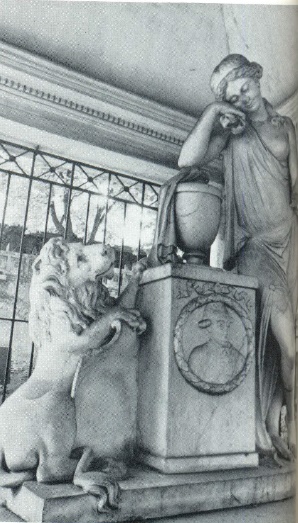

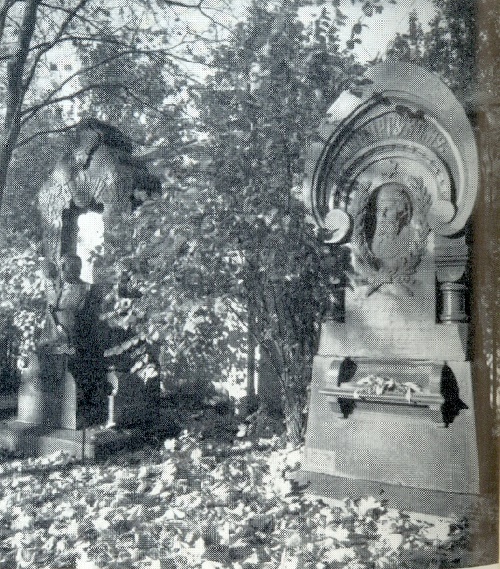

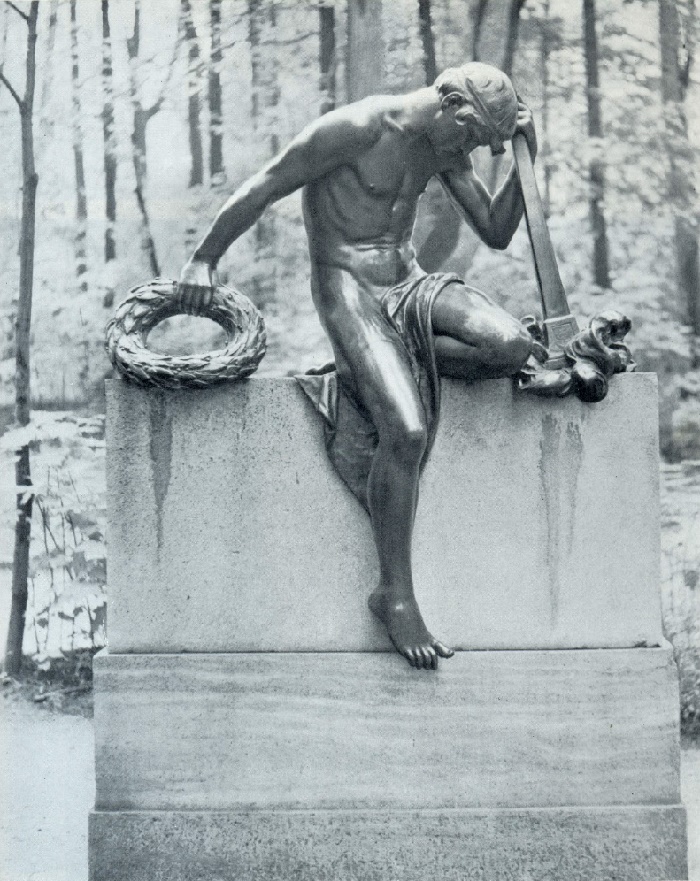

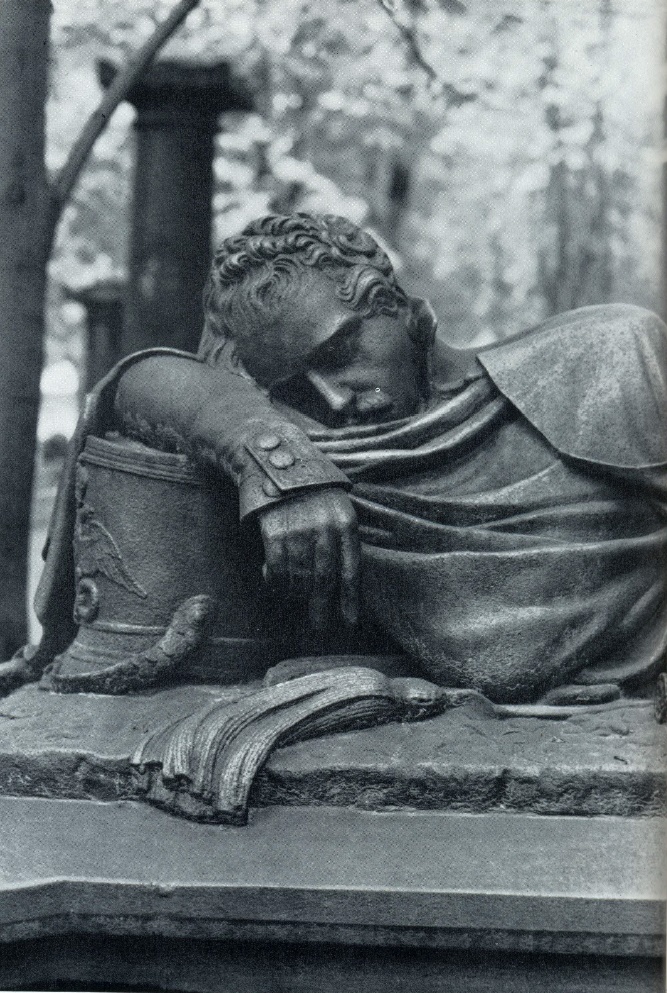

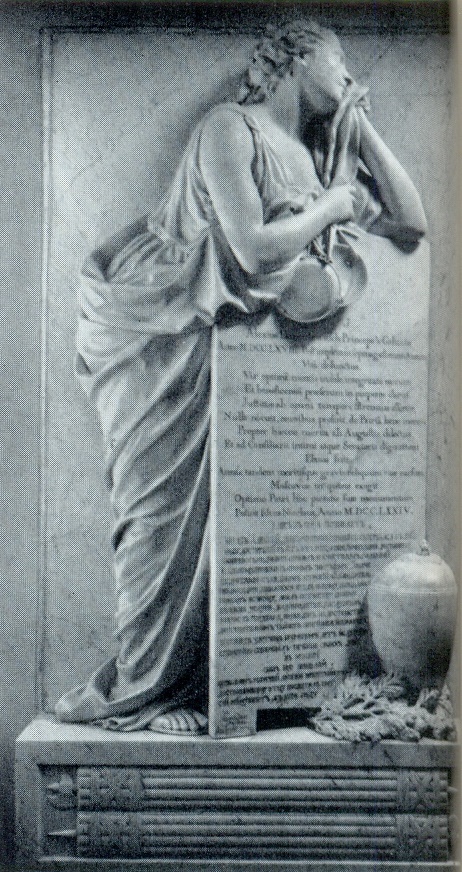

In sculpture and memorial relief, there are often two indispensable allegorical images: Genius, the messenger of death, and the mourner. In the era of classicism, these figures were of importance to the all-European memorial symbol. They are replete with both Russian and Western ancient cemeteries. There are many variations of the image of the mourner, including the Russian, however, characterized by a peculiar characteristic. In the Moscow interpretation, it is usually far from the ancient images and, rather, reminds Russian girls of the early nineteenth century, slightly provincial, but very poetic.

In addition to the well-known arsenal of ancient allegories, both in Russian and in Western symbols formed their allegorical forms and images.

Some of them were very common, for example, a broken young tree – a symbol of an early broken life. It is an independent form of a gravestone and as a fragment in the relief or in a three-dimensional solution. The same symbolism is in the broken flower. Called “monuments of the heart”, these motifs present in different versions of Russian tombstones. The lyrical image created by them, as a rule, is very intimate in its content.

Such, for example, is the tombstone of the captain of the Life Guard Guards cavalry regiment, A. Ya. Okhotnikov, whose name is associated with the name of the wife of Alexander I Elizaveta Alexeevna. His monument in Lazarevsky necropolis is a monolith of red granite with a marble figure of the mourner at the foot of a broken young tree. Below, in the arcuate gleam of the stone, is a broken anchor – a symbol of crumbling hopes.

In the Russian tombstone, with all the drama of the theme, we almost never see the embodiment of horror before death. This feature of the national memorial image brilliantly presented in the works of the great masters of Russian sculpture of the era of the classicism.

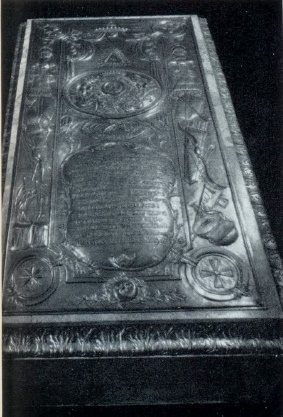

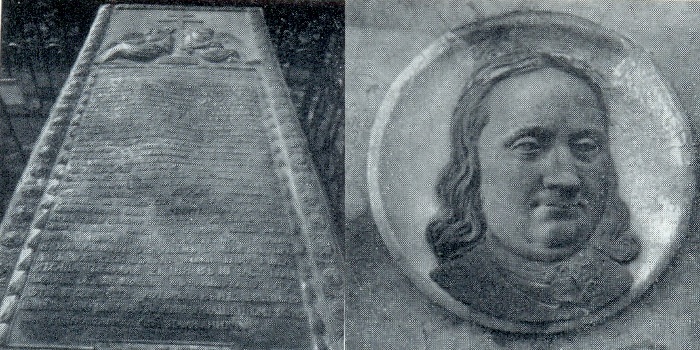

The main task of the baroque epitaph is to sum up the human life, from which a moral lesson is learned for the living. On this basis, created epitaphs both for noble and high-ranking officials, and for people of a more modest social status, including women. It is the life of the first, set forth as a kind of track record, is an example for imitation, following which one can achieve great ranks and immortal glory.

In the Baroque era, seeing the world in bright contrasts, life is likened to a lush bloom, followed naturally by withering-death, opposed to life, as a light of darkness. The trembling expectation of the Last Judgment, combined with the request for prayer, is the lot of people who are not noticeable. The unshakable confidence in the equally worthy reward of heaven, as well as the honors received on earth, are the lot of the highest nobility.

In fact, it is the experience of death that gives each deceased the right to teach. A pious lesson of its inevitability can be given by any deceased. The baroque epithet addressed to a conditional passer-by, to some man in general, somewhere between the beginning and the end of his life path. A passerby should look at the image of a person in mortal darkness, and then mentally imagine his remains underfoot. After hearing this lesson, touched passer-by should pray for the deceased and think about his own demise. The tombstone looks like a kind of window or door to a different world, a world of darkness, permeable mentally and impenetrable physically.

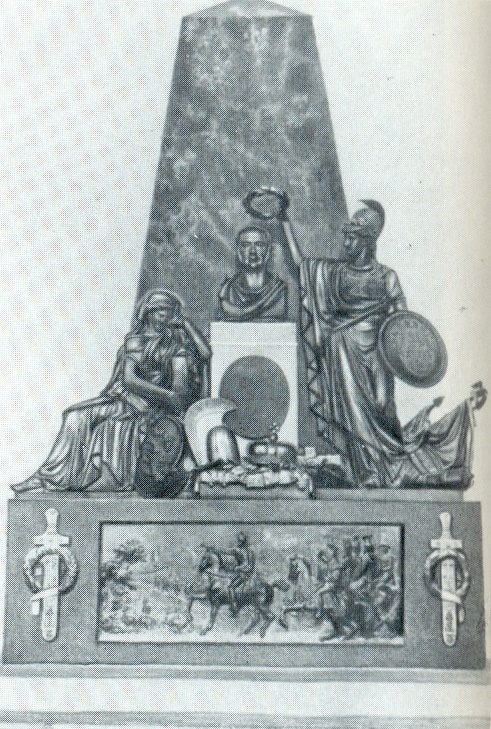

Multi-figured tombstones develop the theme of glorification of the deceased and mourning. In sorrowful pathos, the old man raises the dead infant to the sky, sending it the question “why?”. The soon-won sentimentalism will reject the expression of sorrowful pathos in sculpture (but not in the epitaph). However, the road to calm elegance, the expression of purely personal feelings laid by the monuments, will finally confirm their right to expression.

The glorification of virtues and great deeds is formally put forward in them to the fore, and the theme of personal grief remains on the second. Initially, male tombstones are emotionally more reserved than female, distinguished by deliberate didacticism and demonstrativeness.

Meanwhile, the boundary of 1790 was the time of the emergence of new trends in Russian culture in general. The type of gravestone praising the valor of the deceased is leaving to revive in the era of patriotic upsurge after 1812. Male tombstones, created around 1800, already belong to the expressive direction, distinguished by a dramatic experience of death and an open expression of personal feelings. Such tombstones cease to differ from women’s – the theme of mourning becomes the only one expressed in a memorial sculpture.

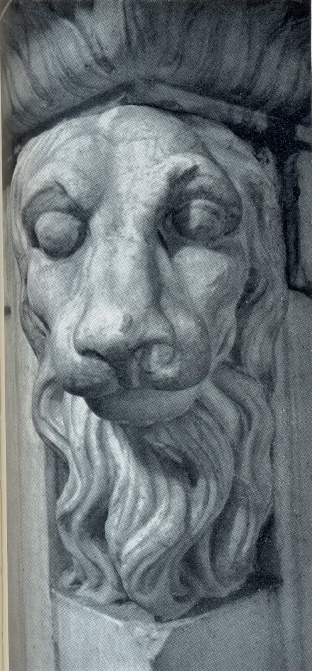

A common feature of the classic images of the deceased is their detachment from the world of the living. They are in the world of eternity and do not meet with the viewer. Satisfaction with the consciousness of the fulfilled debt is on the faces of men. This corresponds to the main task of tombstones, the function of glorification. They seemed to be frozen halfway between the world of the living and the world of eternity. From this series – the portrait from the Stroganova gravestone, lyrically spiritualized, designed to arouse sympathy of the viewer. This is more a sentimental work, indicating a combination of new and old features in the monuments of the expressive direction.

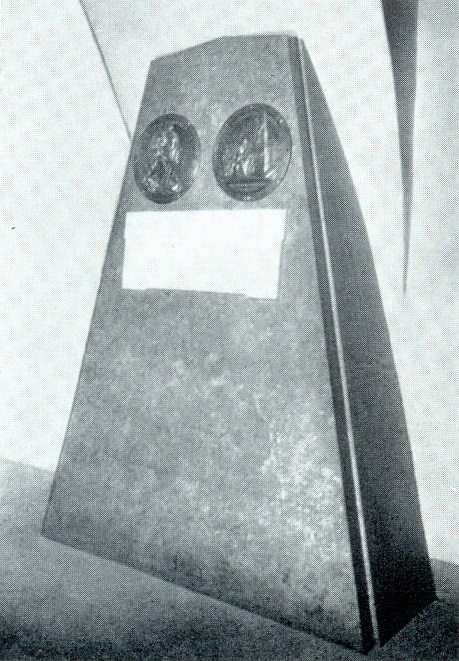

At the beginning of the XIX century in the creation of mass gravestones are important changes. In the manufacture of expensive monuments finally pass from limestone to granite and marble, corresponding to the Empire style. The beauty of the polished faces is more in line with the ideal of geometricity. The place of images of real coffins painted up to direct naturization occupied abstract symbols – urns, obelisks, columns, and pyramids. These new monuments directed upwards, turning to the sky the view of the visitor of the cemetery.

The new epitaph also shows a change in the value system in society. What continued to be truly appreciated in earthly life: ranks, orders and so on, like the ideals of serving the Fatherland, departs in the epitaphs. The deceased gives an example of “heartfelt piety” alive, and service merit (like everything worldly) remains on the earth.

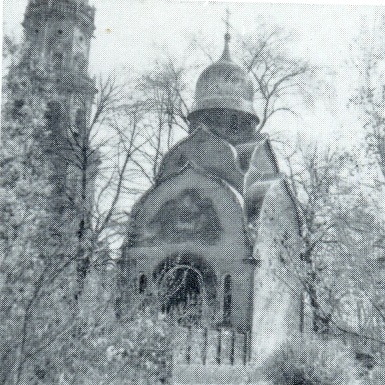

The cemetery and the tombstone established on it are no longer the place to meet the patrimonial ambitions and worldly glorification of the dead. Particularly, religious and family values become the main in the monuments of the new era. Love for God and fellow man, especially for family members, is the main virtue of the ideal person of the new era, and the only important one after death. The ideal of the age is an angel in the figurative sense of the word, a person not of this world, but a body belonging to it. In life, they reveal to the people around them the image of heavenly perfection. And after death they become angels in heaven, the keepers of the relatives left on earth. Their transition to another world is quiet and invisible. They no more belong to the living world, standing on the verge of the earthly and heavenly worlds.

Traditionally, the death of children, young people and girls portrayed beautifully. “As an angel, with her beauty and meekness She flourished here in the world …”. The existence of those who have reached middle or older age is much more difficult. Destined to experience on themselves that earthly life is “a heavy prisoner”, and its destiny is “rebellion and vanity”. All their lives they suffered from the imperfection of this world. But at the same time, passionately mystical craving for the unattainable beauty of the world of heaven. This vision of the world is especially characteristic for the Nikolayev era, the time of mystical romanticism, which does not believe in achieving harmony on earth.

The living and the dead are in constant prayer contact. The living always aspire to look beyond the world of another, and the dead look from heaven to those who remain on earth. Close relatives and friends, all who have and continue to have a spiritual connection with the deceased. The grave is a special place for relatives and only for them, and not for the edification of the offspring. The epitaph addressed to those who, possessing a sensitive heart, are able to empathize with grief. The living ones seem to surround the monument with a ring, from here they are closer to the sky, where the deceased is. “Above this dull stone unite the sensitive crown forever.” The monument with the grave is constantly in the hearts of others. And the gravestone itself symbolically corresponds to this monument in the souls: “Part of my heart this stone covers.”

The predominant emotional feature of the epitaphs of the second quarter of the 19th century is the feeling of mystical longing for heavenly perfection. As opposed to the calm elegiac sadness of the beginning of the century.

“Terrestrial life as a heavy captivity,

The land is a rebellion and a rush. ”

Cemetery sculpture allegory and pathos

source: Russian memirial sculpture. Moscow “Art”, 1978