Ancient Russian tomb sculpture by unknown masters

Ancient Russian tomb sculpture by unknown masters

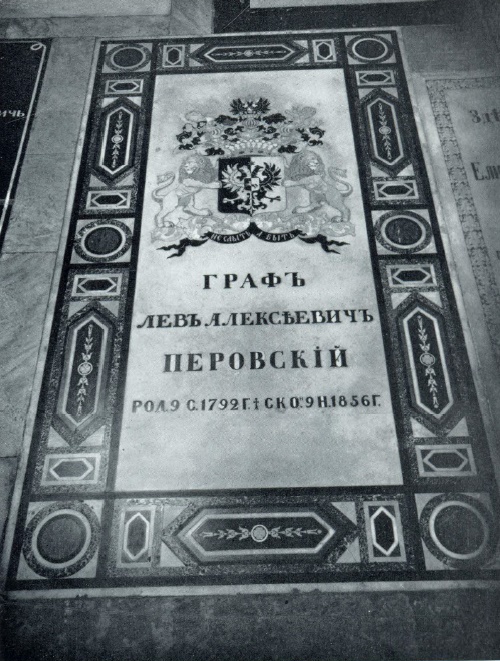

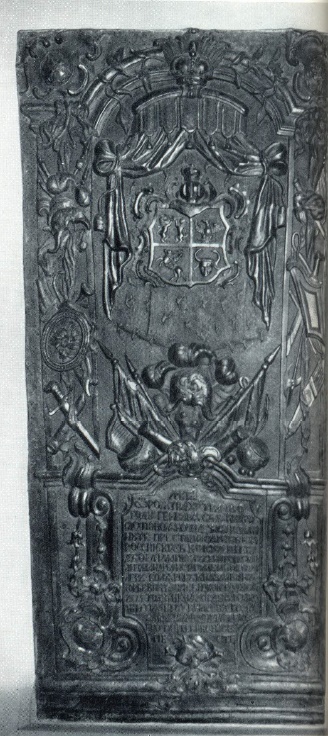

Ancient Rus knew certain types of tombstones in which co-existed varieties of architecture of small forms and applied art. Since the XVIII century the tombstone was a synthesis of sculpture and architecture of small forms. Sometimes it also included a mosaic and a mural. Sculpture was usually the composition of the allegorical statues or a portrait of the deceased. Besides, in the memorials of this period there were other genres. So, in individual reliefs, you can find elements of the landscape, and everyday scenes, and even historical scenes. In addition, various heraldic and allegorical signs characterizing the personality of the deceased.

With the adoption of Christianity, to the cult of ancestors added the faith in the “second coming” and “resurrection from the dead on the day of the Last Judgment”. This inevitably led to the rejection of the incineration, for if the body is burned, “the soul will have nowhere to return.”

Accordingly, the graves of the princes of the nobility began to be performed in tombs, sarcophagi, stone, brick and wooden. Sometimes built in the churchyard, and later even transferred to temples.

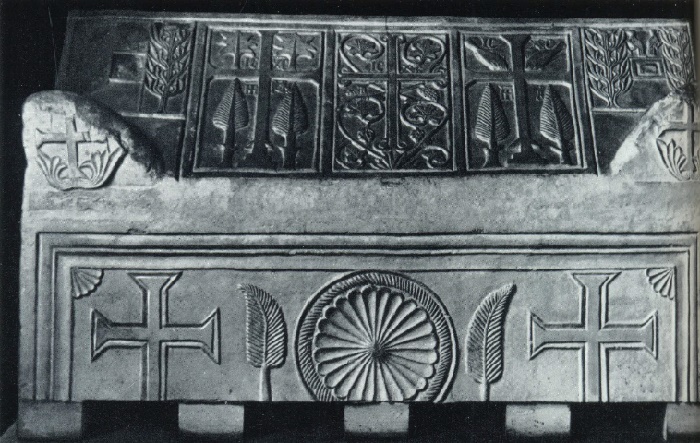

The most significant monument among the Kiev sarcophagi is rightly considered to be the marble sarcophagus of the Grand Duke Yaroslav the Wise (978-1054), whose reign continued and reached its highest point the heyday of Kievan Rus. The creation of this sarcophagus dates back to the 10th-11th centuries.

The study of the sarcophagus began a long time ago, but so far its history is fraught with many mysteries, attracting the attention of archaeologists and art historians.

The sarcophagus itself is an interesting artistic example of a monumental relief, carved from a solid block of white polished marble with grayish-blue horizontal veins. Also, masters carved its lid from the solid block. The planes of the sarcophagus, with the exception of the southern side wall, are abundantly decorated with bas-relief ornament of an excellent design. It includes Greek crosses, charisms, wreaths, rosettes, cypresses, palm branches, vines and bunches, as well as birds and fish. All this, indeed, is close in style to the “sarcophagus of Olga” and has a Christian-symbolic meaning characteristic of Byzantine art.

In addition, there are several surviving sarcophagi, attributed to the era of Kievan Rus X century. They are in the Kiev Historical Museum of Ukraine, and another, in the State Architectural and Historical Reserve “St. Sophia Cathedral.” However, both of them are stone boxes with straight walls and lid, rather primitive and not having any signs or reliefs.

The absence of the sign of the cross shows that there buried princes or guardians even before the adoption of Christianity. One of the sarcophagus in the St. Sophia Cathedral relates to Prince Svyatoslav, killed by the Pechenegs in 972 and who was still a pagan. Three other sarcophagi, exhibited in the St. Sophia Cathedral, represent not only historical, but also undoubted artistic interest.

The material itself is red slate (pyrophyllite shale); many architectural and decorative details were made from it in the Church of the Tithes and the St. Sophia Cathedral. During the excavations on the site of the Tithe Church, researchers also discovered the workshops for the processing of slate slabs. Already in the XI century in Kiev there were Russian master-stone-cutters, who made numerous slate sarcophagi for the Kiev nobility. Among them, along with the smooth-walled, are sarcophagi, entirely covered with bas-reliefs, similar to those decorated with architectural details from the same slate.

Meanwhile, among decorated with reliefs of marble tombs there were several even in one Tithe church, but only a few of the remains of that large and diverse material on art came to us, which found its application and successfully developed in Kievan Rus.

Crosses, wreaths and cypresses are early Christian funerary motifs, also known from the murals of Roman catacombs. Palm branches are signs of glorifying the deceased’s merits. Birds sitting in the trees near the quadrangular “basins” are an image of the souls of believers, quenching the spiritual thirst from the living source of faith. The vine, wrapping the cross on the central part of the composition of the northern half of the lid, is the allegory of Christ himself. He said to the disciples: “I am the true vine, and you are the branches […] My father is the winegrower …”

Besides, the fish motif symbolizes Christ. First, according to the famous evangelical scene of saturation of the crowd with five loaves and two fish. Secondly, the word “fish” in Greek consists of the initial letters in the words “Jesus Christ the King of the Jews”. The inscriptions, according to the Gospel legend, nailed to the cross over the crucified Christ and denoting his guilt, for which he was crucified as an impostor. The Greek letters on both sides of the lid also mean the name of Jesus Christ, the formula “the light of Christ shines out all”, as well as the Greek word “Nika”, that is, victory (the victory of Christianity).

The other, southern half of the lid, decorates even lower embossed ornament, not graphic, but soft. This relief type of braids of two ribbons, very peculiar, as if embodying infinity, not having a beginning or an end, framing the cross. Such a composition of the cross marks the “tree of life”, by analogy with the biblical, advanced rod of “the high priest of Aaron the brother of Moses.”

The motif of the “prosperous cross” was spread very early not only in Byzantium, but also in the Christianized Transcaucasus among the Armenians and Georgians, since the Byzantine figurative motives roamed throughout the Christian East. The classical image of such a cross is on the Korsun gates of the 11th century in the side-chapel of the Nativity of the Virgin in Novgorod Sophia. At the edges of the lid of the sarcophagus, around the rectangular “pools”, beautifully curled palm branches. The lower southern wall has no relief, on it only on top there is a marking of the fragments of the wickerwork.

The end faces of the lid of the sarcophagus, playing the role of the pediment of the whole composition, have identical images of the charisma placed in the wreath and two curly serpentine stems with heart-shaped ends that connect the central wreath with the crosses on the acroteria. But the crosses surrounded by cypresses on the lower end parts are somewhat different in motives. In one case, around the cross, there are depicted stylized vine branches, in the other branches of a palm tree. And also palm branches support the “advanced crosses” on the side faces of the acroteri. Similar motifs exist in the composition of the end part of the slate sarcophagus attributed to Princess Olga.

The mastery with which these reliefs are performed is still striking with its taste, compositional coherence, subtle understanding of design and technical perfection of execution. These are truly royal tombs. Their authors were great masters, possibly seeing all the variety of forms and ornaments of Byzantine tombs.

Ancient Russian tomb sculpture by unknown masters

source: Russian memirial sculpture. Moscow “Art”, 1978